Not a cholera patient lies at the last gasp but I also lie at the last

gasp,

My face is ash-color'd, my sinews gnarl, away from me people retreat.

-Walt Whitman, "Song of Myself" (954-956)

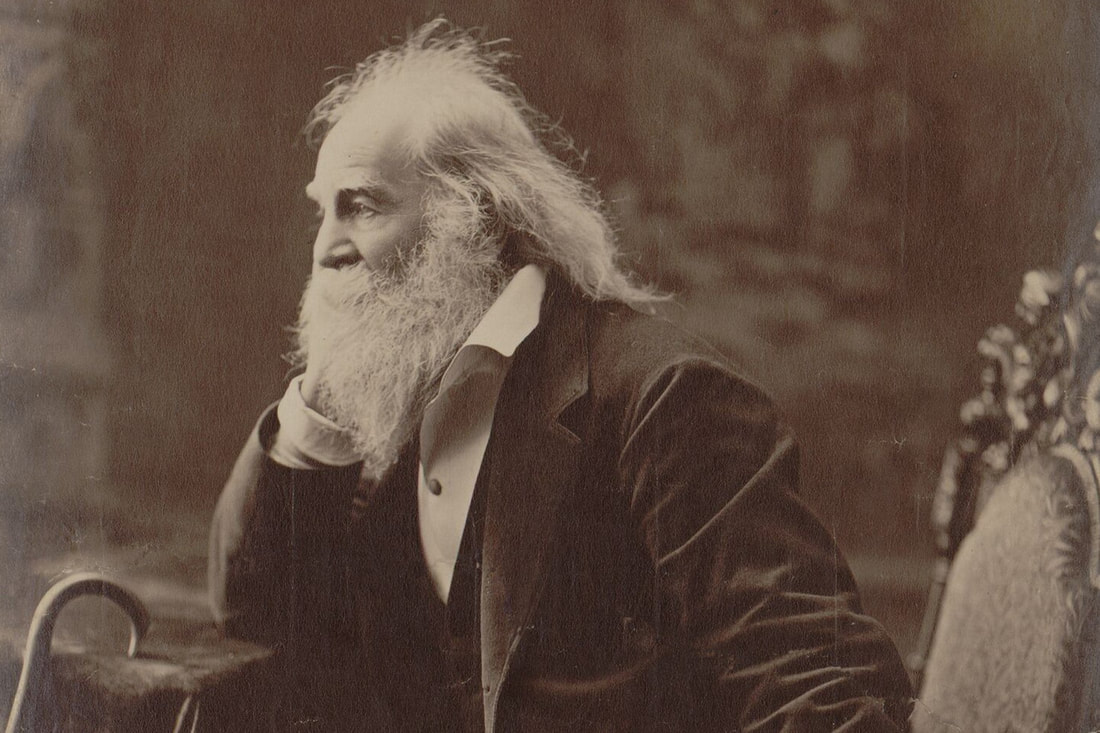

Although cholera was not a major poetic topic for Walt Whitman, perhaps, no other poet's style on either side of Atlantic mimicked better the stream and flow-like symptoms of cholera in poetry than the Brooklyn poet, whose free-verse form and parataxis appropriately suit a poetic representation of cholera. This chapter's epigraph comes from "Song of Myself," a poem known in part for its exploration of the universal self and nature. Part thirty-seven of "Song of Myself" marks the first and final time in the poem when the speaker mentions cholera. Yet it is a crucial moment that shows the speaker's vulnerability, his/her fear of pestilence. In the lines above, the speaker places his/her body next to a cholera-infected patient to experientially connect with their pain and suffering. In the poem, the word "gasp" prompts us to visualize the speaker straining to catch his breath or gasping for air: "I also lie at the last / gasp" (953). The line break between the two monosyllabic words "last" and "gasp" emphasize the fragmentation of the lyrical breath of this enjambed phrase, further accentuating the speaker's struggle for air. Appearing alone in its own line, the word "gasp" also connotes a sense of urgency. The speaker emphasizes a type of corporeal transformation: "My face is ash-color'd, my sinews gnarl, away from me people retreat" (956). As a poetic voice and patient, the speaker becomes a vehicle for cholera. As a patient, the speaker appears to carry the disease: his "sinews [are] gnarl" evoking deformed body (956). While as a poetic voice, the poem is a literal conveyor of what of the symptomatic nature of cholera. The above epigraph implies that what people retreat from is the idea of cholera, the death and anguish it may bring to people. Whitman's "I" stands in for all readers. Thus, we too vicariously experience the pain and suffering of "sinews gnarl[ing]" and the fear of infection that compels us and others to "retreat" (956). Whitman lived through three major cholera outbreaks in the nineteenth-century, but he did not write many poems on the subject. Cholera, however, was a significant part of the regular news cycle and poetic production of periodical writers.

Along with Whitman's lyrical compassion for cholera patients came his great suspicion of medicine and the small group of New England elite physicians that treated cholera (Scholnick 249). Whitman turned elsewhere for healing methods, including Thomsonianism (e.g., the notion that the body is composed of four elements: earth, air, fire and water); homeopathy (e.g., the treatment of disease by small doses of natural substances that in a healthy person would produce symptoms of disease); and Grahamism (e.g., the practice of vegetarian dietetic system) (Scholnick 249). On June 1, 1846, Whitman writes in The Brooklyn Eagle of these treatments, "their excellence is nearly altogether of a negative kind.-They may not cure, but neither do they kill-which is more than can be said of the old systems. They aid nature in carrying off the disease slowly-and do not grapple with it fiercely, and fight it, to the detriment of the patient's poor frame, which is left, even in victory, prostrate and almost annihilated" (Journalism 392-393). Whitman claimed that it is best to "inspire the patient to draw from the healing powers of nature itself," a task that Whitman as a poet would take up in the six editions of Leaves of Grass (Scholnick 250). On the one hand, Whitman's skepticism toward conventional medical practice and the lack of medical consensus in the scientific community for treating and containing diseases like cholera motivated his turn to nature as a restorative source. On the other hand, the visible devastation of cholera and its documentation in newspapers during its major outbreaks particularly in Brooklyn, New York, Whitman's home for twenty-eight years, also informed his skepticism of modern medicine. Havelock Ellis maintains that Whitman benefited from "a practical familiarity with disease and death which has perhaps never before fallen to a great writer" (Ellis 111). Whitman was drawn to hospitals and to sites of death; In the 1840s, he visited cholera victims "whose ravaging disease was almost always fatal" (Aspiz). In fact, according to Whitman's biographer Milton Meltzer, during the first New York City cholera epidemic in 1832, at the age of 13, Whitman "began working for a Brooklyn printer [when a]n outbreak of the dreaded disease cholera, killed thirty-five in Brooklyn and led the Whitmans to move back to the countryside near West Hills. Walt, however, stayed on. Joining the weekly Long Island Star as a compositor. Walt Whitman, however, stayed in Brooklyn to work" (25). Havelock Ellis maintains that Whitman benefited from "a practical familiarity with disease and death which has perhaps never before fallen to a great writer" (Ellis 111). According to Harold Aspiz, Whitman "was attracted to hospitals and to scenes of violent death, apparently visiting cholera victims, whose ravaging disease was almost always fatal, as early as the 1840s."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed